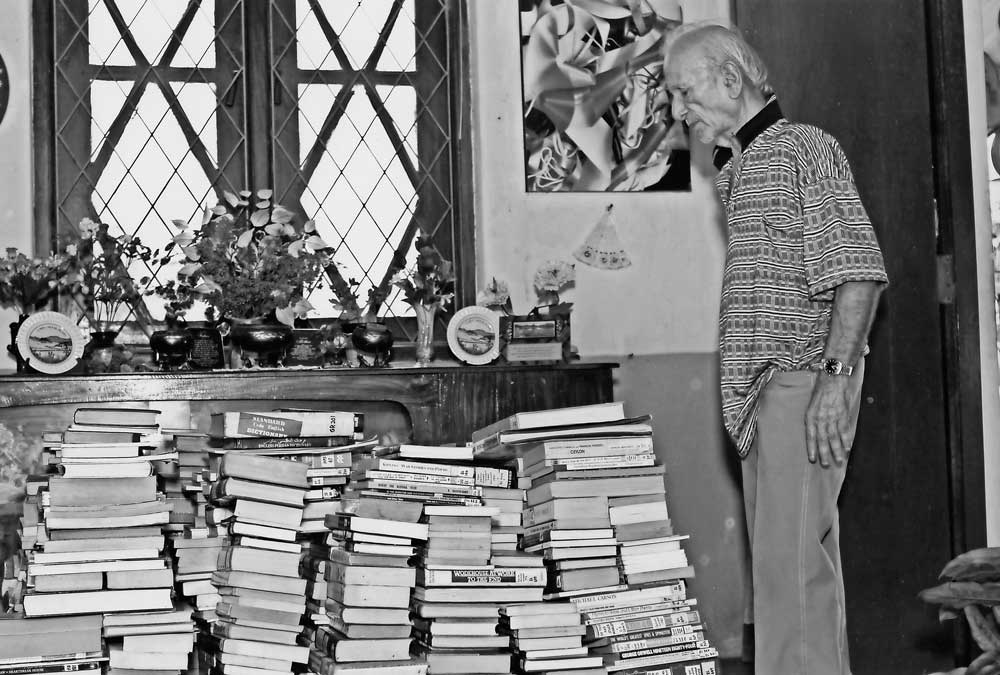

Prolific writer Carl Muller entertained generations of readers with his narrations of life in the burgher community in sri lanka

Compiled by Tina Edward Gunawardhana

and Dhillni Jayatunga

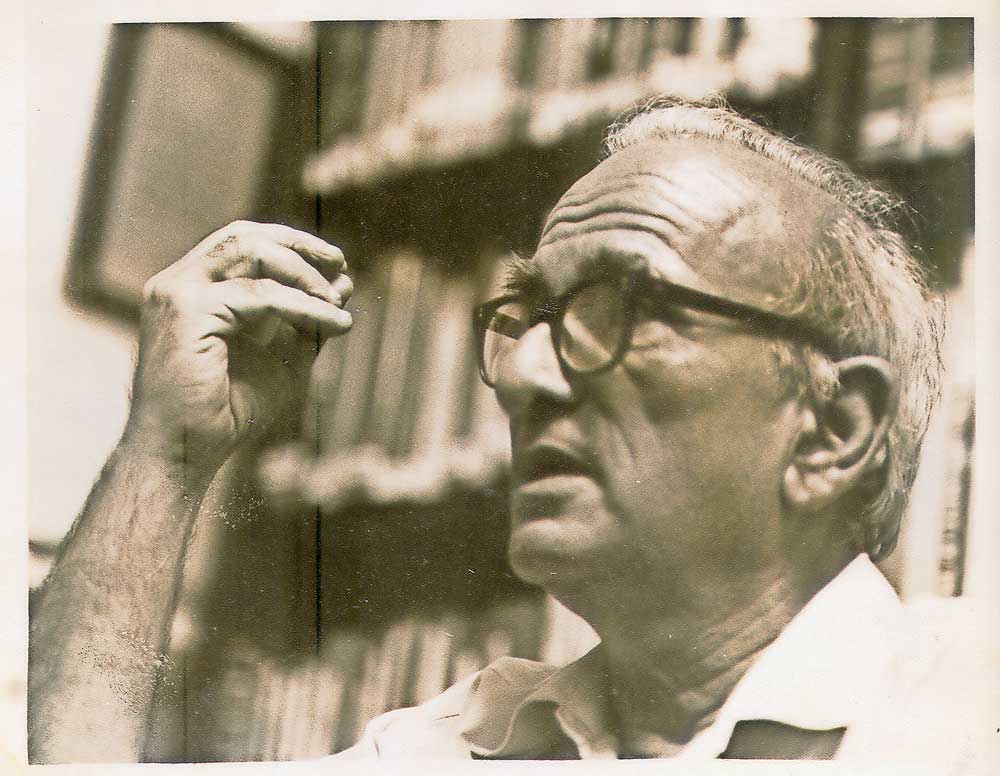

Feted as one of Sri Lanka’s finest writers, Kala Keerthi Carl Muller came to the nation’s attention after the publication of his risqué book ‘The Jam Fruit Tree’. Chronicling the lives of a colourful Burgher family, the book although touted as fictitious did bear some resemblance to real life contemporaries of the author which further served to whet the appetite of his readers who clamoured for more of the same.

Born on the 22nd of October1935, Muller was the eldest of 13 children. His childhood wasn’t the happiest time in his life. As a student, Muller was by no means an academic. He was dismissed from three schools before being enrolled at Royal College. Owing to instability at home he left at the age of 17. The Royal Ceylon Navy beckoned young Muller and he was sent on a tour of duty to the Far-East and India. Upon his return he then went on to serve in the Ceylon Army before joining the Port of Colombo as a pilot station signalman.

Back on civvy street, Muller returned home albeit briefly to discover that the instability and hostility had remained unchanged. Soon after, leaving young Muller to fend for himself, his parents moved to England with the rest of family in tow.

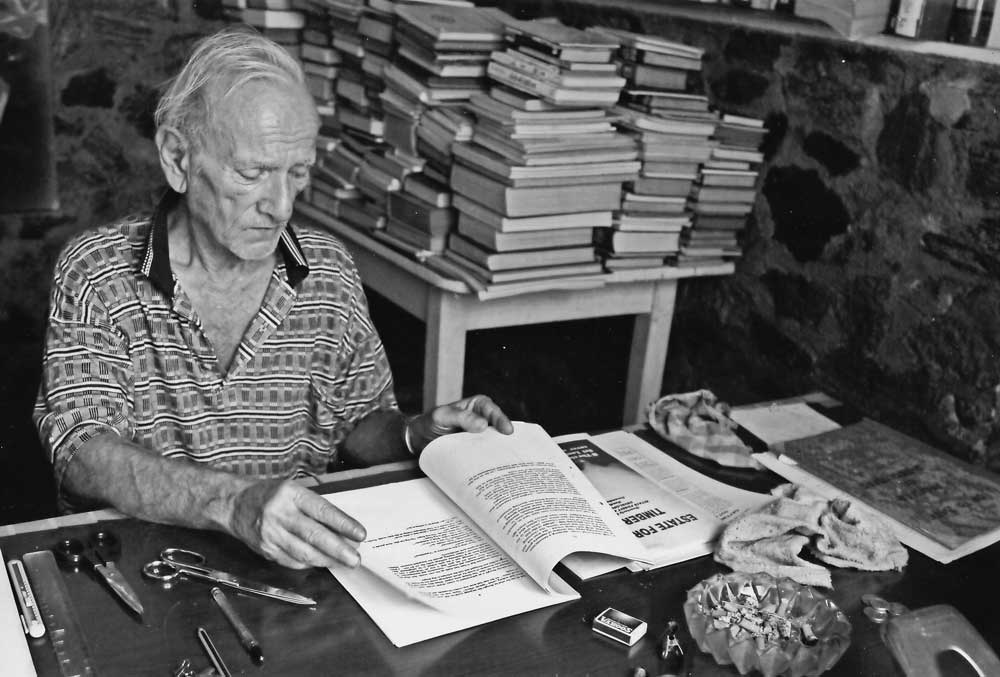

With a scrappy education, Muller realised that the only way out of his situation was to arm himself with an education. The only way he knew and could afford to do so was to become a prolific reader. Muller would read anything he could lay his hands on. Quenching his insatiable appetite to read and acquire knowledge equipped Muller well, for he became a member of the Fourth Estate. Joining the newspaper industry Muller held a variety of posts ranging from cartoonist to sub-editor. However it was as a writer that he excelled at the most. After his marriage, greener pastures beckoned and Muller moved to the Middle East where he worked as a journalist for various newspapers in Bahrain, Dubai, Oman and Qatar.

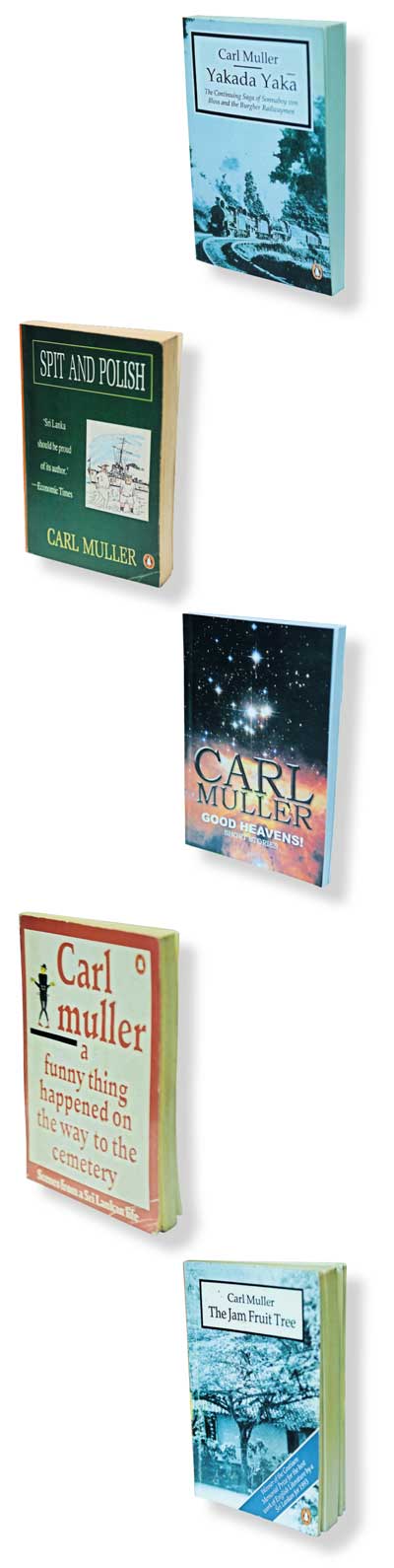

After the publication of ‘The Jam Fruit Tree’, the first of the Burgher trilogy, Muller became a household name especially amongst the reading community. As a Burgher himself he ruthlessly, honestly and unapologetically laid bare the nitty gritty of Burgher life. The use of language, dialogue and nuance in his writing made it one of the best that a Sri Lankan writer had produced. This famous piece of writing earned him the Gratian Prize for the best work of English literature by a

Sri Lankan in 1993. He also became the first Sri Lankan author to be published internationally with this very same book when the editors at Penguin were quick to realise his potential and offered him a multiple book contract.

Muller was perhaps the only writer who in his own unique style of writing laced with liberal doses of sarcasm and wit had documented the trials, tribulations, mannerisms and customs of the Burghers who by that time had all crossed the oceans and settled in far flung lands. The fact that Muller had written about them not in one but in three books gave readers a sense of nostalgia for ‘the good old days’ where the Burghers were quick to ‘put a party’.

The ‘Jam Fruit Tree’ transported readers back to the halcyon days of Ceylon where communities intermingled with ease and life was not a rat race. Many would opine that this book served as a critique of Ceylon in the 1930s where the book transported readers to a bygone era where rickshaws and buggy carts were the chosen method of transport and life was simple.

In the sequel to the Jam Fruit Tree titled ‘YakadaYaka’, Muller documented the lives of the Burghers who worked in the best gift that the British bestowed on Ceylon, the railways. Yakada Yaka related tales of Burghers who worked as engine drivers, railway guards and station masters in quaint villages in rural Ceylon.

The last of the trilogy, ‘Once Upon a Tender Time’ saw Muller write about childhood. It pointed to the Burgher community producing children by the dozen but often forgetting them and considering them a nuisance in the face of more important tasks such as discovering the facts of life. His dedication to documenting the life of his community earned him a term of endearment as the “Burgher of all Burghers”

In his trilogy Muller used distinct phrases and words that were unique to the way Burghers spoke. This annoyed a section of the Burgher community who took umbrage to the fact that Muller has portrayed some of their community of not being able to speak proper English. Some even argued that it bordered on pidgin English. However in a press interview Muller gave in 2008 he responds by saying “My use of the language has met with some scorn by the Burghers who wish to show that they never spoke that way. Their prerogative, I guess. If they are satisfied with the way they speak, they are free to pass off as the Burghers who cannot even claim to have a national language of their own! The Burghers did not speak the way I used the language in my work. I was focusing on one particular family circle. There were the better-spoken Burghers too, but come to think of it, it all depended on their level of education. After all, there was no ‘Burgher language’, but the language taught by the British, to which, there were added hints of the Portuguese tongue, the free use of Sinhala and even Tamil. This would bring on a sort of lilt in the way they spoke. Ordinary speech took no heed of correct presentation at all. Standing sentences on their head seemed to be quite a conversational art!’’

Apart from documenting the life of the Burghers, Muller also excelled in other forms of writing which included historical fiction. As an attestment to that, Muller won the State Literary Award for ‘Children of the Lion’. Drawn back to the genre his readers loved, Muller also wrote ‘Spit and Polish, ‘Maudiegirl’ and the ‘Von Bloss Kitchen’ all laced with stories of life in the Burgher community.

Muller also wrote “A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Cemetery’ and ‘The Python of Pura Malai and Other Stories’ both published in 1995, the same year he wrote and published Colombo: A Novel.

His critics say that when Muller wrote Colombo: A Novel he was at his most cryptic. He wrote about the sexual deviants, rapists, drug dealers, pedophiles and politicians interweaving their lives into historical sketches portraying a Colombo that had no heroes but victims in their own way.

Given his way with words, Muller also wrote poetry, short stories, science fiction, essays and monographs. His books resonated with real people.

Whilst other writers from ethnic minorities documented the strife and vitriol their community faced, Muller on the other hand responded differently to his identity, and his consciousness of its place in a society that had once accorded his community with privilege.

If he didn’t write nostalgically about it, he nevertheless celebrated it frankly, openly and jubilantly. There are enough and more instances in his trilogy where he reflects on the conundrum of being a Burgher: “not quite like them, and not quite like them either” . “Them”, being the native and the European.

Muller referred to his work as factional, rather than fictional, pointing out to the quasi-fictional manner in which he wrote. His work gained local and international attention because he coupled his stories with faction and humor and refused to box himself or be politically correct in his writing. Knowing he could put his talent to good use in stringing words together, he didn’t part with his pen until he was forced to do so owing to illness later on in his life.

Muller wrote for a couple of English newspapers on a wide range of topics although he never got too involved with politics and publishers were only too happy to publish his writings in their columns.

Honouring his contribution to journalism, Muller was bestowed with the prestigious “Kala Keerthi” title by the State.

Of his personal life, little is documented apart from the fact that after a tumultuous and brief married life that ended rather too soon, Muller raised his first son Ronnie more or less on his own. Muller married again at 35 and according to his family, would have celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 2020. From his second wife Sortain, he fathered two daughters, Michelle and Minette and two sons, Jeremy and Destry, who died at the young age of 21. A few years after Destry’s death (he was knocked down by a bus 500 yards away from the family home in Kandy) Muller was instrumental in publishing ‘The Poems of Destry Muller’.

Muller spent the last years of his life suffering from dementia. He passed away in Kandy on the 2nd of December 2019. One of Sri Lanka’s finest writers, he gave the world a unique insight into the much loved Burgher community of which he was one of their best ambassadors.